-

by Rachael Haft

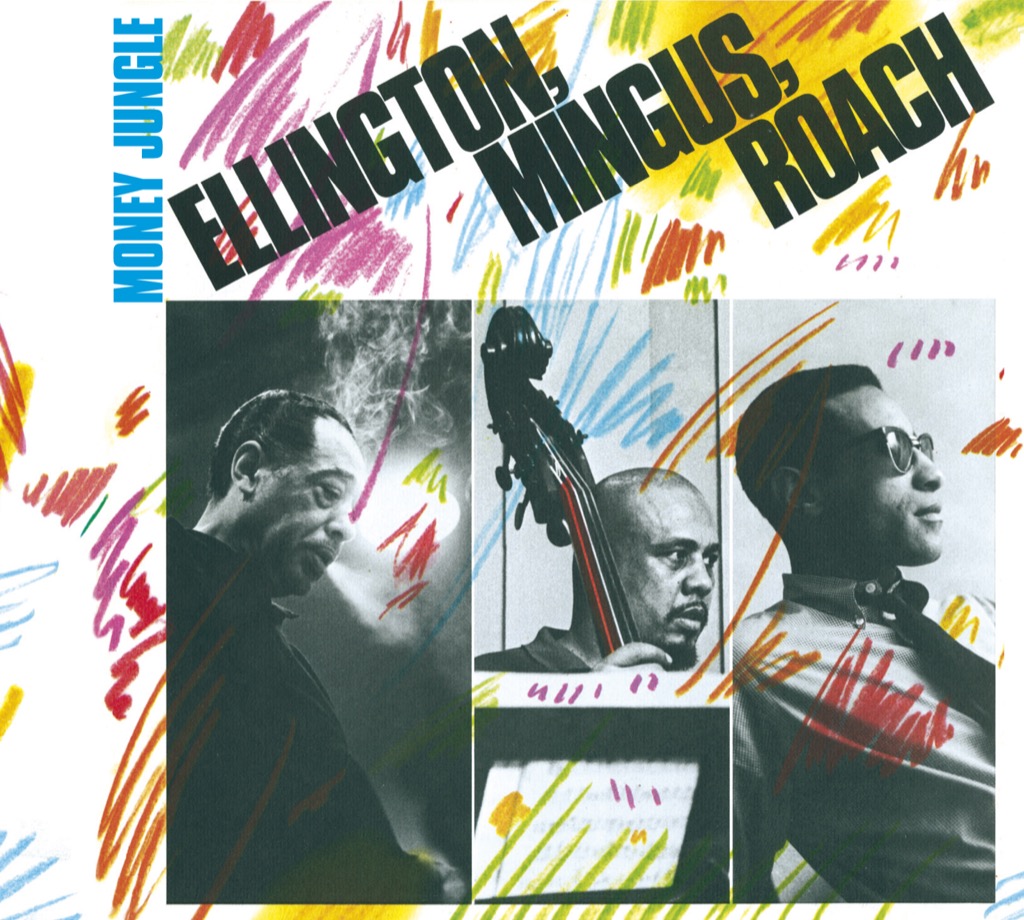

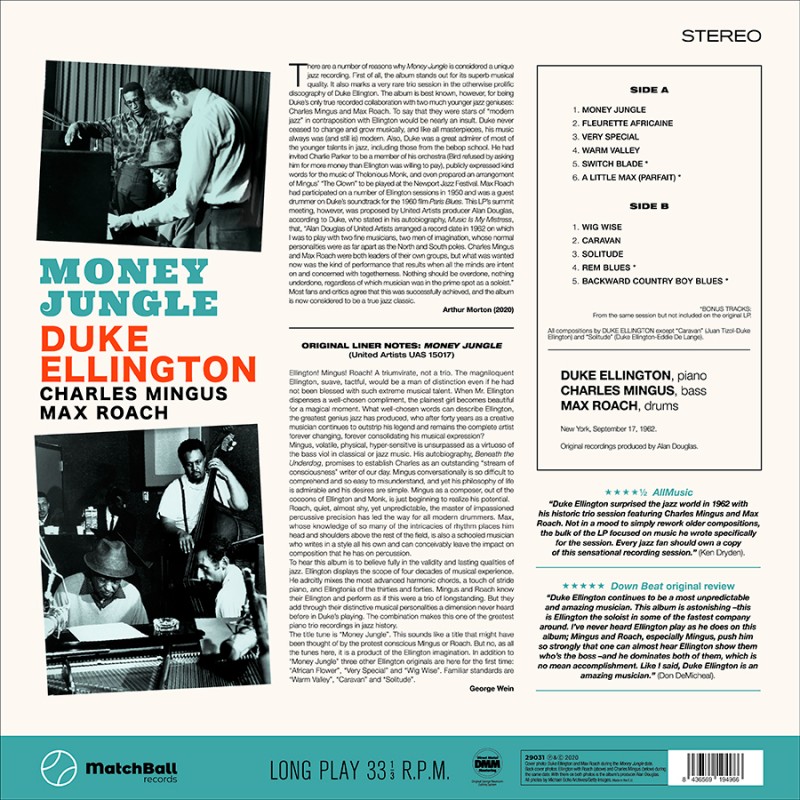

Upon first hearing the opening of Money Jungle’s title track, you might think you are listening to a Japanese Kabuki Theatre performance played on the Shamisen rather than a jazz trio session. Mingus’s unraveling measures of repeated notes set the tone for the whole album. This mood lingers on into Fleurette Africaine in Mingus’s gentle rattling trills, punctuated by sparse and dissonant comping from Ellington. It feels like a haunting lullaby. It’s immediately jarring to hear such invocations from Ellington, a pianist not typically associated with the pared down arrangements of the west coast style or bebop. It was interesting to learn through the Downbeat article on the album’s 50th anniversary that the intent of this trio project was to make an Ellington piano album. Money Jungle is hardly representative of the Duke’s career up until this record. Instead it offers a sneak peek into territories of his genius less exposed to the general public.

The strength of Warm Valley, on the other hand, lies in its captivating refrain. The open spaces of this arrangement invoke images of a lush gospel choir who might populate the refrain with proverbs or other words of great importance to be called out again and again through this memorable musical vehicle. Maybe the warm valley Ellington painted is a place somewhere over the rainbow or the promised land, a place where suffering, trials and tribulations finally come to an end. Even Mingus appears to be deeply moved by it. He is a captive audience until he finally joins in at 1:30 where he leaves behind the percussive streak of the earlier tracks and gently walks by the Duke’s side. The bass even appears to sing along at 1:57, ringing out with moving resonance. Ellington wrote a refrain powerful enough to soothe and subdue the angsty outlier heart of Charles Mingus and bring him into harmony. The tonal center is strong with every stanza leading home into resolution, into a sense of closure, possibly illustrating the idea of Warm Valley as home. The whole track seems to be humming “We’re going home” over and over.

Caravan stands side by side with Money Jungle and Fleurette Africaine with its arresting intro. Max Roach comes in with an unexpected percussive aural palette leaning heavily on the toms, and Mingus pushes the bass to the highest end of its range with rapid fire ostinatos . When I learned that Caravan was a collaborative composition by Ellington and Peurto Rican trombonist, Juan Tizol Martinez, a lot of the elements in this piece began to come together. Max Roach approaches the drum kit as if it were a pair of barrel drums like Congas or Barriles in many of the segments and the latin rhythm is unmistakable in Ellington’s piano phrasing in moments like at 3:10, for example. There is much more going on besides a latin infusion in this piece,however. There are surprising splashes of dissonance, rag elements, dramatically long held notes and broody descending progressions on the low end that make me wonder how much of an impact this album might have had on heroes Thom Yorke and Johnny Greenwood of Radiohead. Caravan, of all the tracks on this record, might encompass the broadest range of moods, moving rapidly through stormy clouds into a playful dance and out again into dark skies, finally closing with the smallest hint of an emotional ballad.

The fact that this entire album was improvised the day of recording is a testament to the mutual respect amongst these three brilliant artists. Their willingness and ability to listen to one another and make space for each other, trusting that something interesting and worthy of scribing into history would result from such an open conversation is what makes this album relevant today and continues to speak not just to jazz artists, but any musician seeking to glean from the riches of collaboration. There is a lesson in the contrast between this collective work and the independent projects of each contributing individual. They could create things together that they could not apart. In Bill Milkowski’s Downbeat article, honoring the 50th anniversary of Money Jungle, he wraps everything up with a quote from keyboardist John Medeski, who explains the importance of Money Jungle as an influential album: “There’s a lot of space for the energy of the communication to be the focal point, not necessarily the notes or the melodies. And that, to me, is the real spirit of jazz. It’s improvised communication, a conversational way of playing. That’s what this album is all about. Hopefully that’s coming back in recording, especially for those who call themselves jazz musicians.”

This conversational approach required a lot of flexibility in all three of these performers, but particularly on the part of band leader, Duke Ellington whose style was forged in the big band era, a wholly different musical landscape than Max Roach and Charles Mingus thrived in with Roach being a major player in the bebop era and Mingus closely connected to third stream and classical studies, though Ellington had done plenty of experimenting with art music in his own way. Few artists could have been better equipped to hold space for new distinct voices than the Duke. Ellington’s entire career had been built on his passion for finding unique voices and writing and arranging music around their particular strengths. He was the king of listening, and he was technically proficient enough to handle even the most out of the box of Mingus’s impulses. Though it was clear that Mingus did push him into new territories that others had not and helped to showcase Ellington’s ability to punctuate and counter with breathtaking phrasing and use his piano to outline and suggest the presence of a fuller band with deliberate and succinct choices in lines and color.

As Milkowski’s Downbeat article illustrated, these three jazz legends gathered to create what is now known as Money Jungle during a very heated time in United States history. Milkowski mentions that the Cuban Missile Crisis, JFK’s assassination as well as Martin Luther King’s famous speech all closely followed behind the release of this album which means that it was created in the heat of a very aggressive fight against segregation. It was in 1961 that the Freedom Riders were at peak activity and Free Jazz was the reigning idiom, chosen by many to herald the cause written on all the signs of protestors. Money Jungle is not a free jazz album. There is a strong sense of tonality to most of the tracks. The splashing of dissonance and juxtaposition of rhythms feel more in keeping with bebop, with Caravan, especially feeling similar to the Mary Lou Williams approach. What is similar in this album to the free jazz approach is a mutual respect for the independent voice, demonstrating a shared belief that, “We can create something beautiful together without trampling on each other or sacrificing the unique talents of the individual.” Could another album have been as successful at realizing this ethos? Could any three players be more aptly matched to each other in values and strengths with Ellington’s nose for arranging for the soloist and Mingus’s focus on collective improvisation? There are times that the bass seems to dominate the aural landscape, like in the title track, for example. It may be unusual to hear the bass playing such a prominent role in a jazz recording, but rather than competing with that space, trying to dominate it or make it redundant, Ellington and Roach build off the ideas being shared with them, honoring the value of Mingus’s voice and lifting it onto a pedestal. At other times, Mingus is unafraid to take a back seat, listen and echo the sentiments Ellington is sharing, such as in “Warm Valley.” In a Little Max, the playfulness of the drummer is showcased and embellished with cheerful dashes of keys from Ellington and the subtlest contributions from Mingus on bass. No instrument or artist is made subservient to the vision of the other. Instead, each artist takes turns both leading and following as it serves the music.

Money Jungle

Duke Ellington, Max Roach, Charles Mingus

released February 1963 by United Artists Jazz.

-

by Rachael Haft

Vulnicura is a collaboration between the Icelandic composer Bjork and beat producer, Arca. It is an internal landscape and narrative, portraying the dissolution of her 13 year relationship with partner, Matthew Barney with whom she has a daughter. It explores the emotional process she went through before and after the breakup. It is the most confessional album of Bjork’s career which spans nearly three decades and 15 or so album releases. The emotional vulnerability of this musical diary is amplified by her use of semi-recitative vocals. The vocals in her track Stonemilker, in particular, are delivered with the utmost reverence for clarity and diction. This is an album in which the lyrics, story and meaning are placed at the highest priority and are at the heart of all the arrangements.

Bjork, is by far, the most important artist and influence of my life, not just because of her musical brilliance, but also because her music, art and activism is representative of what feminine strength means to me. Her lyricism is drenched in emotional intelligence, often instructive on processing difficult emotions, while at other times demonstrating a voracious love and understanding of science, nature and humanity. The lyrics in the track Lion Song are a wonderful example of this. “I refuse it’s a sign of maturity to be stuck in complexity. I demand all clarity.” In this line, Bjork vows to honor and trust her own emotional needs above any outside pressures to accept a situation that is making her unhappy. Her lyrics often reveal a person who is deeply attune to her own values, beliefs and needs, independent from the trappings of misogyny and societal expectations of women. Her exploration of female sexuality and ideas on feminism are rooted in a connection to self rather than a revolt against a mainstream idea of women or an absorption of female liberation ideologies. She offers insight into self actualization, as a woman, through self knowledge and self trust.

“Stonemilker,” the first track of the album and, as it happens, my favorite, is mostly in strophic form written for a string quartet with each verse repeated over the same two melodic themes, one played by the cello and the other by the violin, which sometimes performs in unison and other times harmonizes with Bjork’s vocals and ornaments them. The steady and somber pulse of the upright bass introduces the song and sets the mood. The vocals to this track are expressed in a powerful rhythmic delivery that emphasizes each syllable of the text, creating an environment in which “meaning” is the central pulse of the whole song.“A-juxt-a-pose-zi-shun-neeeng-fay-ates.—Find-our-mu-tu-al–co-or-di-na-ates.”

In “Lion Song,” Bjork’s vocals again are at the center of the arrangement with auto- tuned harmonies using her own voice as texture. The instruments are performed mostly in unison, acting as an extension or reverberation of her words and voice. They feel organically connected to her, rather than separate entities working in collaboration. The syllabical pulse of the cello imitates the intonation of speech. This use of an instrument as a surrogate voice reminds me of the talking drums of ghana. This arrangement may be symbolic of the different parts of a person coming together to find clarity as the lyrics deal with feeling internally divided by complex and varied emotions. “Once it was simple, one feeling at a time. It reached this peak and transformed. This abstract complex feeling, I just don’t know how to handle.” The music video for “Lion Song” further solidifies this imagery of the inner workings of a person, acting and experiencing things together and in response to one another. The footage of her performance includes views of her heart and the inside of her mouth and vocal cords.

The arrangements and composition of each piece in this album is very programmatic, with every element, intentionally selected for the purpose of helping illustrate the lyrical meaning of the text.

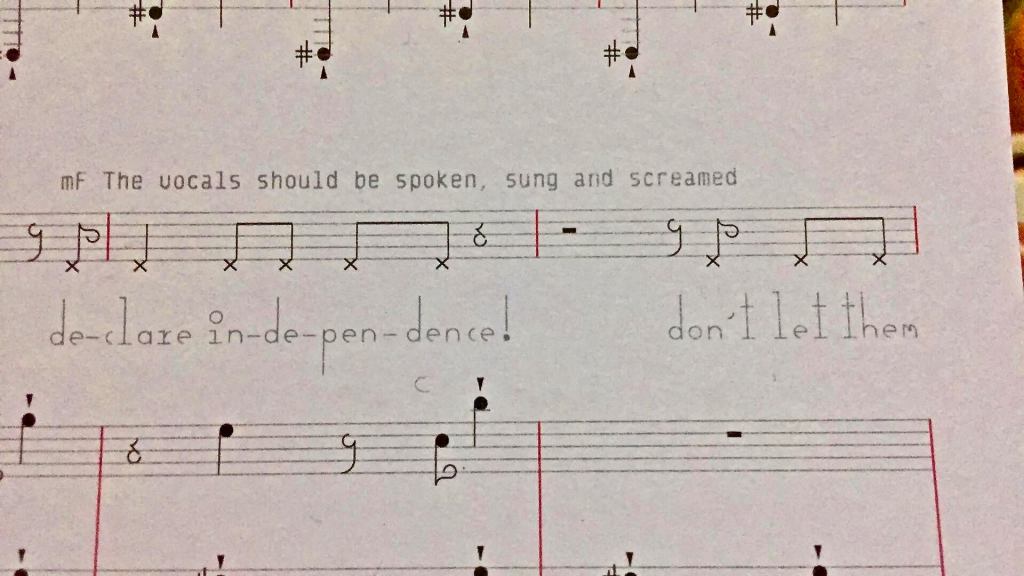

from Bjork’s

34 Scores for Piano, Organ, Harpsichord and Celeste – Björk

https://shop.bjork.com › BjörkIt’s difficult for me to find anything I don’t like about this album. Even pieces that had less effect on me upon first hearing, such as “History of Touches” now move me after repeated listens. The unusual aural landscape and irregular meter make it more difficult to get inside of, but those qualities only contribute to the sensation that you are in a forbidden area and helps to illustrate how intimate the subject matter is.

There are few artists that can stand side by side with Bjork, but Roisin Murphy, who also draws her rich metaphorical lyrics from science and nature, Joanna Newsome whose repertoire is comprised of original folklore and Sevdaliza who uses science fiction and fantasy themes to explore her experience as an Iranian woman all have contributed to a more empowered dialogue around the female experience, for me. It’s also worth mentioning that the list of bands and artists that cite Bjork as an important influence is lengthy and broad. Bjork claims Chaka Khan, Kate Bush, Joni Mitchell, Kraftwerk and Brian Eno as important influences on her work.

I believe Vulnicura to be , not just an important contribution to the genre of breakup albums, sitting alongside Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks with its rich offerings of therapeutic sonic worlds and bare chested language. It is also a deeply respectful monument to female feeling and experience, calling women to honor their pain, needs and desires. In a world that reverberates with shame and judgment around emotion and female experience, Vulnicura elevates emotional wisdom into the intellectual sphere it belongs.

Artist: Bjork

Composer: Bjork;Arca; The Hexan Cloak

Album name: Vulnicura

Date of recording: 2015

Genre: Electronic, Avant-garde, Ambient

-

Music and narrative have always been a powerful duo. They have bolstered the identities of countries, cultures, and communities across the globe, and can be found in the ragas of India, the calypso protest songs of Trinidad, the ballads of Ireland, African American Spirituals, Blues and Gospel and the folk songs of Thailand, Hungary, Russia and so on. It is a universally beloved art form. Each of these genres have an undeniable power and ability to provoke specific emotions in the listener. The music itself teaches the listener what to feel about the stories being told.

The invention of film and television offered new opportunities for musical story telling, and the world has been transfixed by these stories for over a century now. The importance of stories to the human spirit is evident, not just in how universal they are or how long we’ve been writing them, but also in the amount of time we spend listening to them, reading them and watching them.

Through film and television, we learn about the world around us and our place in it. We learn what our culture expects from us and how it feels about us. We learn that we are not alone in our feelings of longing, regret, guilt, disappointment, love, hope or fear. We witness all the possibilities of being human through cautionary tales, stories of triumph over obstacles and stories that challenge our perspective. We learn what we are capable of by seeing people that we identify with and relate to embody and act out a variety roles: hero, villain, soldier, athlete, artist, father, mother, lover, child. We practice imagining and building a different world through genres like science fiction and fantasy. Story is a powerful and effective tool for change.

The term, the Bambi Effect, was coined when the 1942 release of the Disney classic Bambi caused a drastic drop in hunting hobbyists and forever impacted environmental sentiments. Bambi created a heightened empathy for animals by showing the world through their perspective. One vital device they used to accomplish this perspective flip is through the film’s musical score. The film opens with a powerful ballad about the belief in love and belonging that many of us associate with youth and innocence. It’s called ‘Love is a Song That Never Ends” and was written by the late Delaney Bramlett. There is an intrinsic sadness to this song for adult listeners because we have already had to grapple with one of life’s first heartbreaks, the knowledge that our parents will die one day, that we will, that nothing is permanent.

Music is able to illustrate the emotional and internal landscapes of characters, making it easier to empathize and connect with them. Just as Bramlett’s “Love is a Song” tells the audience that Bambi experiences hope and the need for love, connection and safety just like us, the music for the scene in which a hunter kills Bambi’s mother argues that animals are devastated by the loss of their safety and loved ones as much as we are, that they experience fear, sadness and grief. It is a powerful call to imagine the world from another being’s experience. However you feel about Bambi’s effect on environmental views, its impossible not to see how powerful its influence was and how both useful and dangerous such a tool can be.

“It is difficult to identify a film, story, or animal character that has had a greater influence on our vision of wildlife.” -Ralph Lutts (environmental historian)

Many other films can be credited for creating measurable change in the world including Black Fish which forced Sea World to forever close their Orca exhibit. Top Gun caused a 500 percent increase in Navy enlistment. Linklater’s Bernie spurred the release of a convicted killer by creating empathy in the film’s depiction of his struggles. The film Philadelphia is credited for playing a large role in the destigmatization of AIDS. Films like Birth of a Nation, on the other hand, have had a more sinister impact. Its negative depiction of African Americans and positive depiction of clansmen as American heroes resulted in a massive wave of KKK enrollment and increased violence against black people.

Sadly, for much of film and television’s history, these tools that could so easily be used to foster compassion, empathy and understanding have frequently been used to foster contempt and fear. While homophobia and transphobia did not begin with cinema, there are certainly stereotypes, tropes and sentiments that have been fostered and popularized by cinema. You could argue that media popularized homophobia and transphobia. Part of the reason for this is that in 1934 ,The Hays Code was created, effectively banning representation of queerness from film and television. This later relaxed to allow some queer representation, but only if those queer characters were portrayed as villains. Artists who wished to depict their own queer experience were left with few options, but to try to voice their experience through the antagonist. On the other end of things, many heterosexual creators found the use of queer characters exciting and used them to add sensationalism and unease to horror films or absurdity to comedy. This can be seen in films like Psycho, Hannibal or Ace Ventura, Naked Gun, on the other end. Despite the Hays Code ending in 1968, these tropes have lived on leaving the world with a canon of work in which queer coded characters are portrayed either as salacious villains or the butt of a joke.

In the 1936 film, Dracula’s Daughter, one of the first coded lesbian representations appears in the form of…. you guessed it: a vampire. At first glance, this scene seems to start off with a beautiful depiction of a woman moved by feelings of attraction for another woman. The music is not unromantic, its kind of intoxicating, but the tone quickly shifts in this scene, as the music becomes more and more tense and trance like, probably eluding to a vampire’s ability to charm their victims. It ultimately devolves into a horror scene with the strings swelling louder and louder until you hear that classic Bernard Hermann (Psycho) staccato string effect with an innocent young woman screaming. Its crystal clear now that this is not a love story, but a predator and prey scenario.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho itself is an example of a depiction of a queer coded character as a villainous monster. Hermann’s staccato strings have become a symbol of danger and fear that have been referenced by many other horror films. Crossdressing serial killers became a common trope after this film. I want to offer a trigger warning if you haven’t seen this film. It really is a ridiculous and distorted depiction of gender bending, but perhaps it will offer an “AHA!” moment for you as learning about this history of the queer coded villain has done for me. Transphobia and homophobia have start dates. Psycho could even explain( not justify) TERFS’ irrational fears of giving transgender women access to women’s bathrooms. These fears didn’t just pop up out of nowhere, and to me that offers hope that they also have expiration dates. There is nothing natural about fearing the creative expression of gender through clothes, and there is nothing natural or innate to humanity about fearing queerness. Audiences have been manipulated to feel these things through the brilliant use of staccato strings and a captivating story, not just once but repeatedly through passionate sermons and in many horror, crime thrillers.

I cannot save Psycho. The entire story and all of the imagery is problematic, but I did want to challenge myself to try to save a segment of the Dracula’s Daughter scene. I thought there were some elements of the scene that were positive for lesbian representation. Despite the score being quite beautiful, i was curious what a more sincere score might do for the scene, a score without all the suspense and danger cues. One thing you rarely find in queer representation is a dramatic, emotional James Horner string score where two queer characters are getting lost in each other’s eyes. Not sure if this type of score was lost when Horner passed away, but think Pride and Prejudice, Titanic or Braveheart. There is a good bit of intense eye contact in this scene and my goal is to try to make that feel romantic instead of creepy. Here is a Braveheart clip if you have no clue what I’m talking about. A good place to start is around 2:28. Can you hear how the music is conveying that this interaction is important, exciting, beautiful and loaded with emotions? This is what I’m going to attempt to do for my vampire scene.

So here is my go at creating big feels for Dracula’s Daughter. I would not score a vampire movie this way, but I do hope for more big dreamy moments for queer characters fleshed out with orchestral swells. This is, also, by the way, my first attempt at scoring anything, but its why I’m in school so I’m glad I’m getting a jump on it.

If you want to learn more about queer representation in media or are curious about how music and film interrelate, these are the resources I used for researching this project:

I rented this documentary from Amazon Prime and I highly recommend it! Its the history of queer representation and how its progressed through the years. Lily Tomlin is a narrator!

The above video is a video essay by Lindsay Ellis “Tracing the roots of transphobia in pop culture” and these articles:

https://www.looper.com/149503/movies-that-actually-changed-the-world/

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/01/24/bambi-is-even-bleaker-than-you-thought

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.