by Rachael Haft

Upon first hearing the opening of Money Jungle’s title track, you might think you are listening to a Japanese Kabuki Theatre performance played on the Shamisen rather than a jazz trio session. Mingus’s unraveling measures of repeated notes set the tone for the whole album. This mood lingers on into Fleurette Africaine in Mingus’s gentle rattling trills, punctuated by sparse and dissonant comping from Ellington. It feels like a haunting lullaby. It’s immediately jarring to hear such invocations from Ellington, a pianist not typically associated with the pared down arrangements of the west coast style or bebop. It was interesting to learn through the Downbeat article on the album’s 50th anniversary that the intent of this trio project was to make an Ellington piano album. Money Jungle is hardly representative of the Duke’s career up until this record. Instead it offers a sneak peek into territories of his genius less exposed to the general public.

The strength of Warm Valley, on the other hand, lies in its captivating refrain. The open spaces of this arrangement invoke images of a lush gospel choir who might populate the refrain with proverbs or other words of great importance to be called out again and again through this memorable musical vehicle. Maybe the warm valley Ellington painted is a place somewhere over the rainbow or the promised land, a place where suffering, trials and tribulations finally come to an end. Even Mingus appears to be deeply moved by it. He is a captive audience until he finally joins in at 1:30 where he leaves behind the percussive streak of the earlier tracks and gently walks by the Duke’s side. The bass even appears to sing along at 1:57, ringing out with moving resonance. Ellington wrote a refrain powerful enough to soothe and subdue the angsty outlier heart of Charles Mingus and bring him into harmony. The tonal center is strong with every stanza leading home into resolution, into a sense of closure, possibly illustrating the idea of Warm Valley as home. The whole track seems to be humming “We’re going home” over and over.

Caravan stands side by side with Money Jungle and Fleurette Africaine with its arresting intro. Max Roach comes in with an unexpected percussive aural palette leaning heavily on the toms, and Mingus pushes the bass to the highest end of its range with rapid fire ostinatos . When I learned that Caravan was a collaborative composition by Ellington and Peurto Rican trombonist, Juan Tizol Martinez, a lot of the elements in this piece began to come together. Max Roach approaches the drum kit as if it were a pair of barrel drums like Congas or Barriles in many of the segments and the latin rhythm is unmistakable in Ellington’s piano phrasing in moments like at 3:10, for example. There is much more going on besides a latin infusion in this piece,however. There are surprising splashes of dissonance, rag elements, dramatically long held notes and broody descending progressions on the low end that make me wonder how much of an impact this album might have had on heroes Thom Yorke and Johnny Greenwood of Radiohead. Caravan, of all the tracks on this record, might encompass the broadest range of moods, moving rapidly through stormy clouds into a playful dance and out again into dark skies, finally closing with the smallest hint of an emotional ballad.

The fact that this entire album was improvised the day of recording is a testament to the mutual respect amongst these three brilliant artists. Their willingness and ability to listen to one another and make space for each other, trusting that something interesting and worthy of scribing into history would result from such an open conversation is what makes this album relevant today and continues to speak not just to jazz artists, but any musician seeking to glean from the riches of collaboration. There is a lesson in the contrast between this collective work and the independent projects of each contributing individual. They could create things together that they could not apart. In Bill Milkowski’s Downbeat article, honoring the 50th anniversary of Money Jungle, he wraps everything up with a quote from keyboardist John Medeski, who explains the importance of Money Jungle as an influential album: “There’s a lot of space for the energy of the communication to be the focal point, not necessarily the notes or the melodies. And that, to me, is the real spirit of jazz. It’s improvised communication, a conversational way of playing. That’s what this album is all about. Hopefully that’s coming back in recording, especially for those who call themselves jazz musicians.”

This conversational approach required a lot of flexibility in all three of these performers, but particularly on the part of band leader, Duke Ellington whose style was forged in the big band era, a wholly different musical landscape than Max Roach and Charles Mingus thrived in with Roach being a major player in the bebop era and Mingus closely connected to third stream and classical studies, though Ellington had done plenty of experimenting with art music in his own way. Few artists could have been better equipped to hold space for new distinct voices than the Duke. Ellington’s entire career had been built on his passion for finding unique voices and writing and arranging music around their particular strengths. He was the king of listening, and he was technically proficient enough to handle even the most out of the box of Mingus’s impulses. Though it was clear that Mingus did push him into new territories that others had not and helped to showcase Ellington’s ability to punctuate and counter with breathtaking phrasing and use his piano to outline and suggest the presence of a fuller band with deliberate and succinct choices in lines and color.

As Milkowski’s Downbeat article illustrated, these three jazz legends gathered to create what is now known as Money Jungle during a very heated time in United States history. Milkowski mentions that the Cuban Missile Crisis, JFK’s assassination as well as Martin Luther King’s famous speech all closely followed behind the release of this album which means that it was created in the heat of a very aggressive fight against segregation. It was in 1961 that the Freedom Riders were at peak activity and Free Jazz was the reigning idiom, chosen by many to herald the cause written on all the signs of protestors. Money Jungle is not a free jazz album. There is a strong sense of tonality to most of the tracks. The splashing of dissonance and juxtaposition of rhythms feel more in keeping with bebop, with Caravan, especially feeling similar to the Mary Lou Williams approach. What is similar in this album to the free jazz approach is a mutual respect for the independent voice, demonstrating a shared belief that, “We can create something beautiful together without trampling on each other or sacrificing the unique talents of the individual.” Could another album have been as successful at realizing this ethos? Could any three players be more aptly matched to each other in values and strengths with Ellington’s nose for arranging for the soloist and Mingus’s focus on collective improvisation? There are times that the bass seems to dominate the aural landscape, like in the title track, for example. It may be unusual to hear the bass playing such a prominent role in a jazz recording, but rather than competing with that space, trying to dominate it or make it redundant, Ellington and Roach build off the ideas being shared with them, honoring the value of Mingus’s voice and lifting it onto a pedestal. At other times, Mingus is unafraid to take a back seat, listen and echo the sentiments Ellington is sharing, such as in “Warm Valley.” In a Little Max, the playfulness of the drummer is showcased and embellished with cheerful dashes of keys from Ellington and the subtlest contributions from Mingus on bass. No instrument or artist is made subservient to the vision of the other. Instead, each artist takes turns both leading and following as it serves the music.

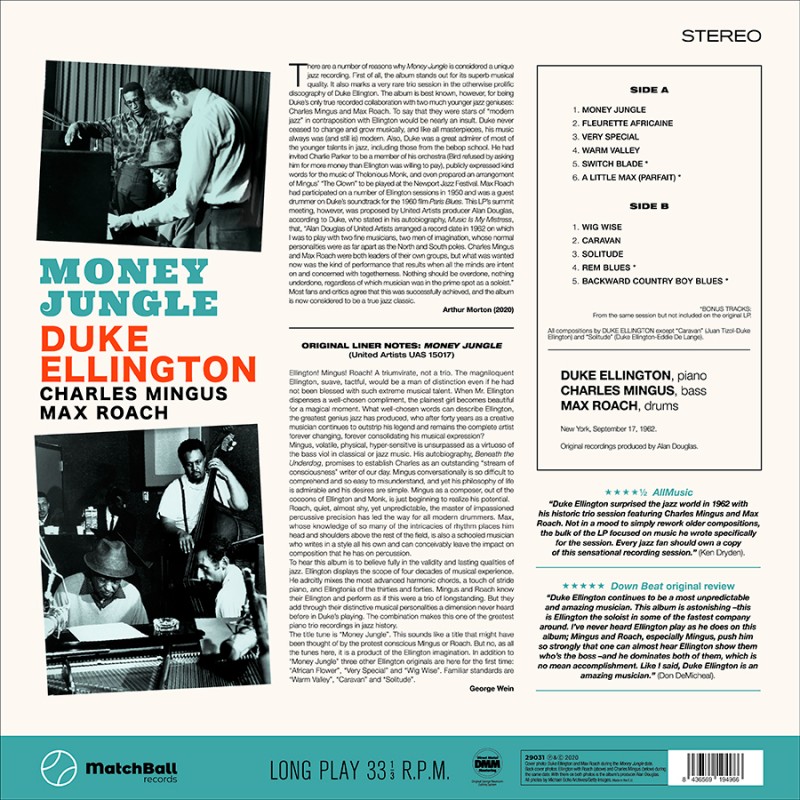

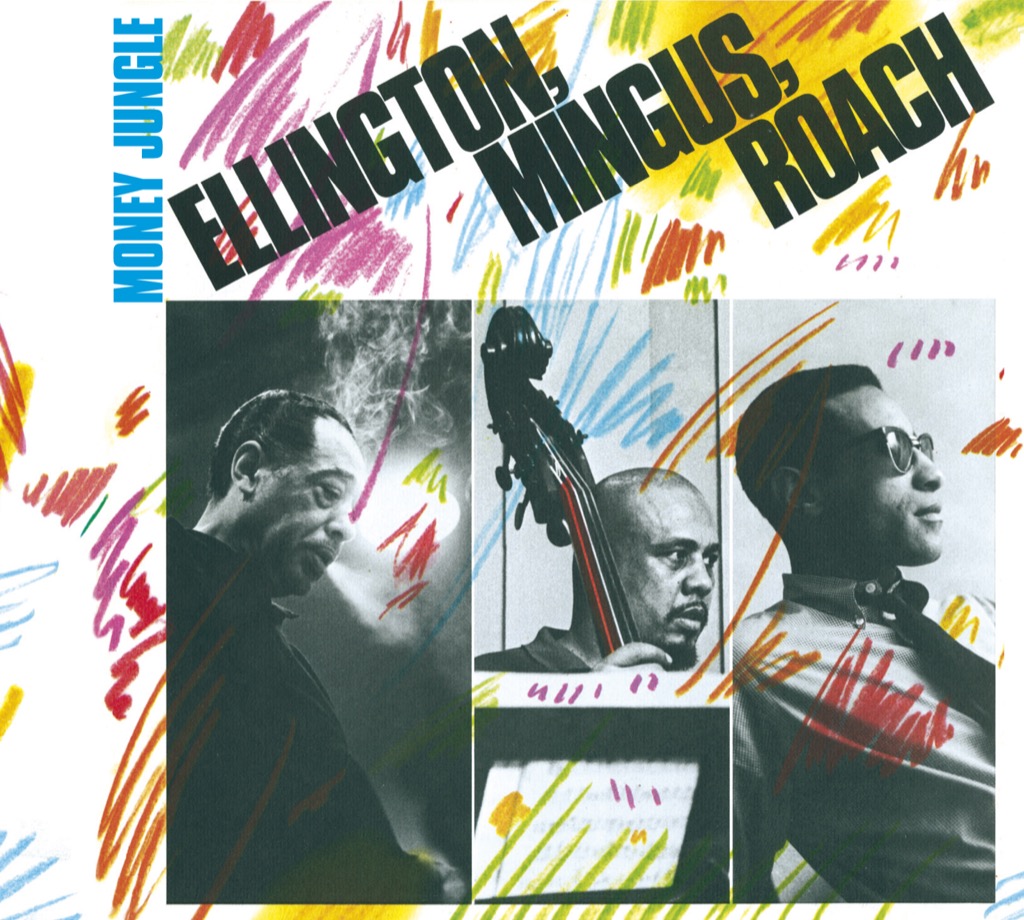

Money Jungle

Duke Ellington, Max Roach, Charles Mingus

released February 1963 by United Artists Jazz.

Leave a comment